5 Tenant Screening Red Flags Ontario Landlords Miss ~ How to Catch Them Legally

Table of contents

- The High-Stakes Reality of Tenant Screening in Ontario

- The Two Pillars of Ontario Screening Law: The RTA and the OHRC

- The Landlord's Legal "Dos and Don'ts" Screening Checklist

- 5 Warning Signs to Be Aware Of

- The Solution: A Proactive and Compliant Ontario Screening Checklist

- From "Red Flags" to a "Green Light" Process

- Resources

Get in touch with our team at Zulma Real Estate and let's build something that works.

The High-Stakes Reality of Tenant Screening in Ontario

For residential property owners in Ontario, the tenant screening process is the single most critical risk-mitigation activity they will undertake. A mistake made at this stage is not a simple error; it can escalate into a significant financial and legal crisis. The eviction process in Ontario, governed by the Residential Tenancies Act (RTA) and adjudicated by the Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB), is notoriously long, complex, and costly. Placing a problematic tenant can mean months of lost rent, legal fees, and potential property damage, with landlords facing a difficult, protracted process to regain possession of their unit.

This high-stakes environment creates significant anxiety for landlords, particularly concerning "professional tenants" who exploit the system. This fear, however, often leads to a critical over-correction: landlords abandon a systematic process and instead rely on "gut feelings," "general appearance," or other subjective judgments. This intuitive approach is not only unreliable but is often illegal, placing the landlord in direct violation of the Ontario Human Rights Code (OHRC).

The most dangerous red flags, therefore, are not just the subtle deceptions by an applicant, but also the fundamental misunderstandings of Ontario's laws by landlords themselves. This report analyzes the five most commonly missed red flags and details how to establish a legally compliant, robust screening process that is far more effective than instinct. A legally defensible process is, in fact, the most effective way to identify and avoid high-risk tenants.

The Two Pillars of Ontario Screening Law: The RTA and the OHRC

Before identifying any red flags, it is essential to understand the two discrete legal frameworks that govern rental housing in Ontario. Landlords must operate within the strict boundaries of both.

The Residential Tenancies Act (RTA), 2006

The RTA primarily governs the relationship after a tenancy agreement is formed. However, it sets the stage for the screening process in critical ways. The RTA dictates the terms of the tenancy, requires the use of the Ontario Standard Lease for most tenancies, and outlines the only permissible reasons for ending a tenancy. Most notably for screening, Section 14 of the RTA renders any "no pet" clause in a tenancy agreement void. Understanding these non-negotiable terms from the outset prevents landlords from attempting to screen for or enforce void conditions.

The Ontario Human Rights Code (OHRC)

This is the critical law for the screening phase. The moment a landlord publicly advertises a unit for rent, they are a "housing provider" and are fully subject to the OHRC. The OHRC prohibits discrimination in housing based on specific "protected grounds". Landlords cannot refuse an applicant based on:

Race, ancestry, place of origin, color, ethnic origin, or citizenship

Creed (religion)

Sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression

Age

Marital status or family status (e.g., having children or being pregnant)

Disability

Receipt of public assistance (e.g., Ontario Works, ODSP)

There is one major exception to these rules: if the owner or their family (which includes a tenant advertising for a roommate) will be sharing a kitchen or bathroom with the occupant. In this "roommate" scenario, the RTA does not apply, and the OHRC's anti-discrimination rules are not infringed. However, for any self-contained unit, including a basement apartment with its own kitchen and bath, all OHRC rules apply without exception.

The Landlord's Legal "Dos and Don'ts" Screening Checklist

The apparent conflict between a landlord's need for due diligence and the OHRC's restrictions creates confusion. The following table translates the complex legal requirements into a practical, scannable checklist for a compliant screening process.

5 Warning Signs to Be Aware Of

1. The Inconsistent or "Too Perfect" Application

What is Often Missed: Landlords, often in a rush, accept application packages at face value. They fail to spot the subtle inconsistencies that signal active, practiced deception. This includes:

An application listing one address while the credit report lists another.

A "current landlord" reference who is overly enthusiastic, vague, or desperate to have the tenant move out.

Pay stubs or employment letters that look off—containing mismatched fonts, formatting errors, or personal email addresses (e.g., @gmail.com) for the "HR Department".

The phone number for the "employer" or "landlord" goes directly to a friend's cell phone.

These are the hallmarks of a fraudulent application, designed to pass a superficial check.

How to Catch It Next Time (The 360-Degree Verification):

A professional screening process is built on the principle of "Trust, but Verify." The verification itself is a powerful deterrent; bad tenants are often afraid of a thorough application process and will screen themselves out when they see one is required.

Verify the Landlord Reference: This is the most frequently faked document.

Tactic: Always call the previous landlord, not just the current one. The current landlord may lie to get rid of a problem tenant.

Tactic: Verify Ownership. This is a critical step. Use an online land registry (like OnLand in Ontario) to search the property records for the reference's address. This allows the landlord to confirm if the name provided as the "landlord reference" matches the name on the public property title. If they do not match, the reference is likely fraudulent.

Tactic: Ask specific, non-yes/no questions: "What was the exact monthly rent?" "What date did they move in?" "What was the reason they gave for leaving?" A fake reference (a friend) will have vague, hesitant answers.

Verify Employment:

Tactic: Do not call the phone number provided on the application. Google the company's publicly listed main line or HR department number and call that.

Tactic: Scrutinize pay stubs. Look for inconsistencies in deductions or formatting. Landlords can cross-reference the deductions with current Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) payroll standards to spot fabrications.

Verify the Person:

Tactic: In an in-person meeting or showing, ask to see a government-issued photo ID (like a driver's license). This is not to discriminate based on age, but to verify that the name and date of birth match the application and are correct for the credit check.

2. Evasive, Pushy, or Rushed Behavior

What is Often Missed: Landlords ignore behavioral red flags because they misinterpret them. The applicant seems eager, not desperate. They seem generous, not deceptive. These behaviors include:

Trying to rush the process, claiming they "need a place today".

Offering to pay several months' rent in cash upfront if the screening process is skipped.

Becoming overly defensive, evasive, or hostile when asked for standard documents or consent for a credit check.

Excessive haggling over every standard term, such as rent and deposit amounts.

How to Catch It Next Time (Differentiating Gut vs. Fact):

This is where landlords must learn to separate an illegal gut feeling from a documented behavioral observation.

Illegal "Gut Feeling" (Discrimination): "I don't like their 'general appearance'", or they have "bad teeth". These are subjective, discriminatory, and grounds for an OHRC complaint.

Legal "Behavioral Observation" (Diligence): "Applicant refused to provide written consent for a credit check". "Applicant offered to pay a $5,000 cash deposit to bypass the reference check". "Applicant became argumentative when asked for a previous landlord reference".

These observations are objective, factual, and a non-discriminatory basis for denial. A quality tenant will understand and respect a professional, standardized process.

Furthermore, the "cash upfront" offer is a well-known trap. A landlord may see it as "de-risking" the tenancy, but the opposite is true. First, in Ontario, it is illegal to collect a rent deposit of more than one month's rent (or one week's, if paid weekly). Accepting more is a violation of the RTA. Second, the cash is a smokescreen. The applicant is buying their way out of a screening process that would reveal a catastrophic history, such as past evictions or no verifiable income. This large cash payment is often the last payment the landlord will ever receive.

3. The Flawed Financial Picture (Looking Beyond the Score)

What is Often Missed: Landlords exhibit a critical lack of diligence in financial analysis. They either:

Accept a tenant-provided screenshot of their credit score from a free app, which is easily faked.

Pull their own credit report but only look at the three-digit score, ignoring the rich data within the report.

See a high income and assume affordability, ignoring the applicant's debt load.

How to Catch It Next Time (Read the Whole Report):

The objective is to assess financial responsibility, not wealth. A credit report tells a story that the score only hints at.

Always Pull Your Own Report: A landlord should never accept a report from the applicant. Using a reputable service (like SingleKey, FrontLobby, Equifax, or TransUnion) is the only way to ensure the data is accurate. This requires the applicant's written consent.

Analyze the Full Report: The score is the least important part. The analysis should focus on patterns:

Payment History: Is there a pattern of late or missed payments on credit cards, car loans, or utility bills? This is a strong predictor of late rent.

Accounts in Collections: Are collection agencies actively pursuing the applicant?. This is a major sign of financial distress.

Credit Utilization / Debt Load: A high income is irrelevant if all their credit cards are maxed out. A high debt-to-income ratio means any small emergency (e.g., a car repair) could result in non-payment of rent.

Address History: Does the list of past addresses on the credit report match the addresses provided on the rental application? If not, the applicant is lying about their rental history.

This deeper analysis helps resolve the paradox noted by many landlords: some tenants with "bad credit" (e.g., high student loan debt but a perfect payment history) are excellent tenants who prioritize rent, while some with "good credit" and high incomes are financially over-extended and miss payments.

4. The "No Verifiable History" Applicant

What is Often Missed: The applicant seems perfect—polite, stable job—but their story is that they are "living with my mom/family" , a "first-time renter", or "new to Canada". There are no previous landlord references to call and no established credit history to check. The landlord, unsure of what to do, takes them at their word.

This is not an automatic red flag, but it is a data void. The "living with family" excuse is also a common tactic used by serial evictees to hide a history of LTB judgments and bad references.

How to Catch It Next Time (Bridge the Data Void Legally):

This scenario presents a direct conflict between law and risk.

The Legal Constraint: The OHRC is explicit: a landlord cannot use a lack of rental or credit history as a reason for denial. Doing so is discriminatory, as it systemically penalizes young people, newcomers, and others who have not had the opportunity to build such a history.

The Compliant Solution: The landlord cannot deny for lack of history, but they are not required to take on blind risk. The solution is to place more (and legally permissible) weight on the other pillars of screening:

Income Verification: This becomes the primary tool. The landlord must be extra diligent in verifying the stability and sufficiency of the applicant's employment and income.

Require a Guarantor (Co-Signer): This is the single best practice for this scenario. A guarantor is someone (often a parent or close relative) who signs the lease and agrees to be legally liable for the rent if the tenant defaults.

Screen the Guarantor: The landlord must then screen the guarantor with the exact same rigorous, documented process as the applicant. This includes pulling the guarantor's credit report (with consent) and verifying their income and debt load.

This approach is legally defensible. The denial is not based on the applicant's lack of history (which is illegal), but on their inability to provide a qualified guarantor (which is a legal, financial requirement). This process also acts as a social filter: a responsible person can almost always find a qualified co-signer. A high-risk individual hiding their past likely cannot.

5. The Landlord's Legal Missteps

What is Often Missed: The final and most dangerous red flag is not in the applicant, but in the landlord's own illegal process. These are ticking time bombs that expose the property owner to complaints, fines, and legal action at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO).

The OHRC Income Trap

A landlord believes they are being diligent by applying a "3x rent-to-income" rule 14 or by immediately disqualifying an applicant upon learning their income source is the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) or Ontario Works.

This is illegal. The OHRC explicitly states that "receipt of public assistance" is a protected ground. Furthermore, applying a strict rent-to-income ratio (like 30%) is also deemed discriminatory, as it is a known proxy for screening out those on social assistance, newcomers, women, and other protected groups.

How to Fix It: Income can and must be assessed, but only in context. The OHRC requires that income information be considered together with credit history and rental references.

Correct, Legal Assessment: "Does the applicant have sufficient income to pay the rent?". This is then weighed against their verified history. An applicant on ODSP with a clean credit report and glowing references from verified landlords is a far lower risk than a high-income earner with maxed-out credit cards and a history of late payments. The whole file must be assessed.

The "No Pets" Clause Confusion

A landlord puts a "No Pets" clause in their advertisement or lease, thinking it protects their property.

This is a critical misunderstanding of the law. Section 14 of the Residential Tenancies Act makes any "no pet" provision in a tenancy agreement void. If a tenant signs that lease, moves in, and brings a dog the next day, the landlord cannot evict them for that reason.

How to Fix It: The legal nuance is specific:

Before Tenancy: A landlord can ask "Do you have pets?" on the application. Because the RTA does not govern the pre-tenancy selection process, a landlord can (quietly) choose another qualified applicant who does not have pets. (This does not apply to service animals, which are a disability accommodation).

After Tenancy: Once the lease is signed, the "no pet" clause is meaningless. The landlord can only seek eviction (by applying to the LTB) if the pet itself becomes a problem (e.g., causing substantial property damage, making excessive noise that interferes with reasonable enjoyment, or being an inherently dangerous breed).

The Condo Exception: The only major exception is if the rental unit is a condominium that has its own by-laws prohibiting pets. In this case, the condo corporation's rules are enforceable, and the landlord can evict a tenant for violating them.

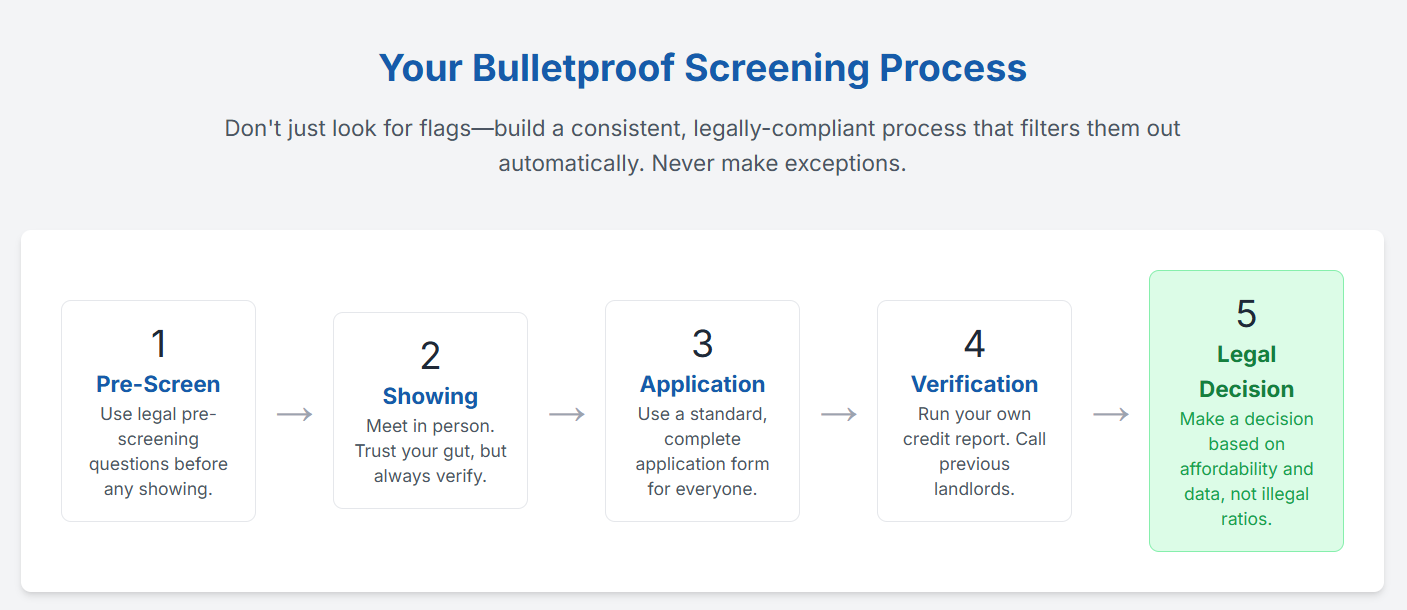

The Solution: A Proactive and Compliant Ontario Screening Checklist

Landlords should stop "hunting" for ambiguous, subjective "red flags." This approach is unreliable and legally perilous. The solution is to build a professional, documented, and legally compliant screening system applied equally to all applicants. A robust system is not an obstacle; it is a filter. It provides a "green light" for high-quality tenants (who appreciate the professionalism) and causes fraudulent applicants to see their own red flags and screen themselves out.

A "gold standard" process includes these steps:

Create Written Rental Criteria: Before posting an ad, the landlord should define their objective, non-discriminatory criteria. (e.g., "Must provide positive references from verified past landlords," "Must demonstrate a credit history of responsible bill payment," "Must have verifiable income sufficient to cover rent," "No smoking in the unit").

The Pre-Screening Call: On the initial call, state the criteria: "Our standard process for all applicants includes a full application, written consent for a credit check, and verification of income and landlord references. Are you comfortable with that?" High-risk applicants will often hang up.

The Application Package: Use the Ontario Standard Lease and a supplemental Rental Application (such as Form 410 from the Landlord Self-Help Centre) to gather the necessary details for verification (past addresses, employer info, references, and written consent).

The 360-Degree Verification:

Pull an independent credit report.

Call previous landlords and verify their ownership via public land records.

Call employers via publicly listed HR numbers.

The Interview: An in-person or video meeting is not for judging "appearance" but for documenting objective behaviors. Are they clear and respectful? Do they ask reasonable questions about the unit, or strange ones (e.g., "Do the screens come out of the windows?").

The Decision: Make the final decision based only on the pre-defined written criteria, applied equally to all. Document the non-discriminatory reason for any denial (e.g., "Denied due to documented history of late payments on credit report," or "Denied due to negative reference from a verified previous landlord"). This documentation is the landlord's best shield.

From "Red Flags" to a "Green Light" Process

In Ontario's complex and highly regulated rental market, "gut instinct" is a landlord's greatest liability. A focus on subjective "red flags" is a losing game that invites legal challenges and financial losses.

The most effective risk-management strategy is to shift from a reactive hunt for red flags to a proactive system of professional, documented, and legally compliant verification. A robust screening process is a filter that works in two ways: it provides a clear "green light" for the high-quality, responsible tenants who respect professionalism, and it forces high-risk, fraudulent applicants to screen themselves out. In Ontario, a good process is a landlord's best and only true protection.

Resources

Uba Abraham

The visionary founder of Zulma Real Estate, established in 2022.

Recognizing the need for proactive asset management and preventing long-term value decline, Uba founded Zulma Real Estate to offer superior property management that preserves and grows investment value. The firm aims to partner with 5,000 homeowners and investors to ensure asset appreciation by 2030.

Join Zulma Community. Connect, Share, Grow!

- Get fast answers in active discussion forums

- Join or create a club and grow your investor network

- Access free calculators and essential investor resources

- Discuss industry news and insights with like-minded peers